Paul was very definitive regarding his purpose and methodology in ministry:

Paul was very definitive regarding his purpose and methodology in ministry:

“Though I am free and belong to no man, I make myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all men so that by all possible means I might save some. I do all this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings” (1 Cor 9:19-23).

In the 1st century CE three boundary markers: circumcision, food laws, and the Sabbath (1), distinctly separated the Jewish and Gentile worlds. While these distinctions had existed for centuries, they did not become problematic until Paul’s mission efforts in the Greco-Roman world produced Gentile converts. The book of Acts chronicles these struggles (Acts 13:49; 14:2, 21). Even though Peter believed the promise of salvation was for everyone, (Acts 2:39) he was personally hesitant to go to the God-fearing household of Cornelius (Acts 10: 9-23). Subsequently, he had to defend his choice to his Jewish brothers (Acts 11:1-18). Even later he had difficulty fellowshipping non-Jewish converts in Antioch (Gal 2:11-12). Eventually the problem created by integrating Jews with non-Jewish converts escalated and necessitated the need for the Jerusalem conference of Acts 15. This conference concluded with the construction of a letter based on the holiness code of Leviticus (Leviticus 17-26). Meant to disarm the varying schools of thought it was sent to Gentile Christians in Antioch, Syria and Cilicia (Acts 15:23).

Paul was the undisputed leader in taking the gospel to the Greco-Roman world (Acts 9:15; 13:36). We have an account of two rather lengthy ministries with Greco-Roman churches. He worked with the church in Ephesus for three years (Acts 20:31) and the church in Corinth for 18 months (Acts 18:11). While it is impossible to know the entirety of his teaching to the Corinthians, we do know they sent questions to Paul after his departure. Specifically they were concerned with how, as Christians, they should relate to the world around them and how they should conduct themselves among other Christians. One of the questions centered on eating meat as forbidden by the Holiness code of Leviticus and the conference letter (1 Cor 8:1). In a masterful way, Paul shifted the focus from specifics to the overall objective—sharing the gospel. His approach to evangelism was his willingness to adapt himself to others for the salvation of the lost (1 Cor 9:19-23).

In three examples Paul demonstrated his willingness to modify his teaching and his actions to fit an “occasion.” The first example focused on Christians and the Jewish food laws. Under normal conditions Paul would have supported the directions of the Jerusalem conference letter regarding the food laws in Judaism (Acts 15:29). However, in response to their question about eating meat offered to idols, he told them there were “two occasions” where it would be permissible: (1) if meat was bought in the market place, the Christian should not ask questions about its origin (1 Cor 10:25); and (2) if an unbeliever invited a Christian to eat meat with him, the Christian was not to ask about the origin of the meat (1 Cor 10:27).

In the second example Paul adapted his teaching on circumcision to fit an “occasion”. The Jerusalem conference had made it clear that circumcision was not a salvation issue and should not be required of Gentile converts. Paul supported this stance in his letter to the Galatian churches (Gal 5:6, 12), using uncircumcised Titus as an example (Gal 2:1-5). He also argued against the merit of circumcision in his instruction that the Corinthians remain in the state they were called (1 Cor 7:19). When Paul decided to convert Jews, Timothy accompanied him. On this “occasion” he ordered Timothy be circumcised (Acts 16:3) so that he would be effective in converting Jews.

In the third example Paul adapted his activities to fit an “occasion” in his reaction to criticism. He went to Jerusalem to visit James and the elders and reported the success of the Gentile ministry. James and the elders applauded the success of this ministry (Acts 21:17-20), however there was concern that Paul was teaching the Jews who lived among the converted Gentiles to turn away from Torah (Acts 21:21). This criticism might not have been justifiable, so in order to preserve Paul’s credibility, the Jerusalem church leaders told Paul to pay the purification expenses of four men (Exod 29:37; Lev 12:2-8; 13:6; Num 19:14). By this action, Paul would prove the reports untrue and verify that he was “living in obedience to the law” (Acts 21:24). Because Paul had been involved with Gentiles some might have thought him “unclean” (Acts 21:26). Consequently Paul not only paid the requested amount, he joined in the purification rites. He felt the “occasion” demanded he join in the purification rites and, in so doing, supported the teaching of Torah. Paul’s personal involvement demonstrated his respect for the law.

Conclusion

Even though other illustrations of the occasional nature of scripture are threaded throughout the New Testament, these three examples underscore Paul’s evangelistic approach: I have become all things to all men so that by all possible means I might save some.

Footnotes:

1 The Sabbath and special days like Pentecost were important to Paul (1 Cor 16:8). His visits to the synagogue on the Sabbath could have been for both evangelistic purposes and his personal respect for observing the Sabbath (Acts 13:5, 14; 16:13; 17:2, 10; 18:7).

2 Peter’s response in Acts 10:14 showed the importance of eating and associating with non-Jews.

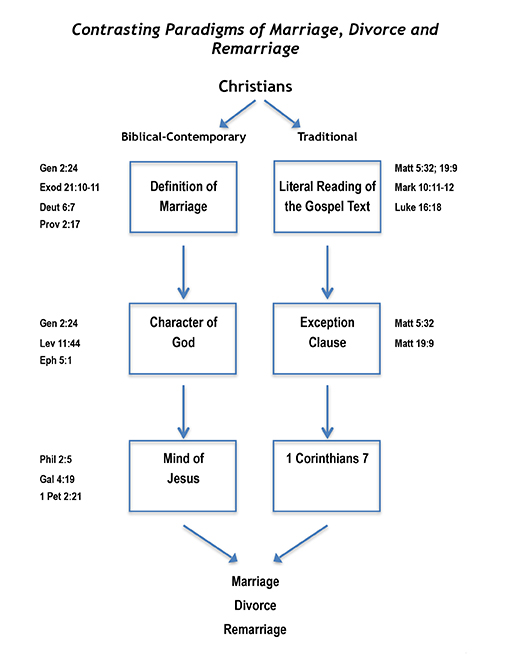

Using the character of God and the mind of Jesus as the benchmark, Paul declared what conduct was right or wrong. In an ideal world, divorce would be a non-issue but the world is anything but ideal. We are a flawed people living in a flawed world. People divorce. Perhaps instead of imposing our opinions on how various situations should be viewed, we should take a cue from Paul. When we approach all of life through the lens of the character of God and the mind of Christ, our sight is clarified. Such was the goal in writing my book,

Using the character of God and the mind of Jesus as the benchmark, Paul declared what conduct was right or wrong. In an ideal world, divorce would be a non-issue but the world is anything but ideal. We are a flawed people living in a flawed world. People divorce. Perhaps instead of imposing our opinions on how various situations should be viewed, we should take a cue from Paul. When we approach all of life through the lens of the character of God and the mind of Christ, our sight is clarified. Such was the goal in writing my book,  Our new book,

Our new book,  For the past 19 years Lynn and I have been conducting relationship and marriage conferences. Our work has taken us across this nation, into foreign countries, and into the lives of thousands of Christian men and women struggling with the issues of divorce and remarriage. Many had experienced the trauma of divorce yet many others were in places of leadership and were wrestling with the practical application of the biblical text. As a result, over fifteen years ago I determined to prayerfully restudy the topic.

For the past 19 years Lynn and I have been conducting relationship and marriage conferences. Our work has taken us across this nation, into foreign countries, and into the lives of thousands of Christian men and women struggling with the issues of divorce and remarriage. Many had experienced the trauma of divorce yet many others were in places of leadership and were wrestling with the practical application of the biblical text. As a result, over fifteen years ago I determined to prayerfully restudy the topic.

The couple is united (glued) together and cannot be separated (Gen 2:24; Matt 19:6).

The couple is united (glued) together and cannot be separated (Gen 2:24; Matt 19:6). In the example of the observance of the Lord’s Supper in the gospels, we find the following: (a) people reclined around one table (Matt 26:20); (b) it was done in the upper room (Luke 21:12); (c) it was taken in context with a common meal , the Passover, (Matt 26:21, 26); (d) it was taken with thanksgiving (Matt. 26:26); (e) it was observed on a Thursday night (Matt 26:17); (f) it involved twelve people (Matt 26:20).

In the example of the observance of the Lord’s Supper in the gospels, we find the following: (a) people reclined around one table (Matt 26:20); (b) it was done in the upper room (Luke 21:12); (c) it was taken in context with a common meal , the Passover, (Matt 26:21, 26); (d) it was taken with thanksgiving (Matt. 26:26); (e) it was observed on a Thursday night (Matt 26:17); (f) it involved twelve people (Matt 26:20).